- Calling their demeanor the spoiled system also works

- The spoils of the system are that now the unions threaten and try to dictate who their bosses will be

- The “grand bargain” was out the window decades ago. Now unions have their cake (Civil Service) and eat it too (aggressive political involvement)

- The law of concentrated gain and diffuse pain ruled “debate” about reforming Iowa public employee collective bargaining law

———————————————————————————————————

This commentary, in the form of links and excerpts with our annotation, raises some points about the public employee system and the recent passage of collective bargaining reforms in Iowa. This report will be in two installments.

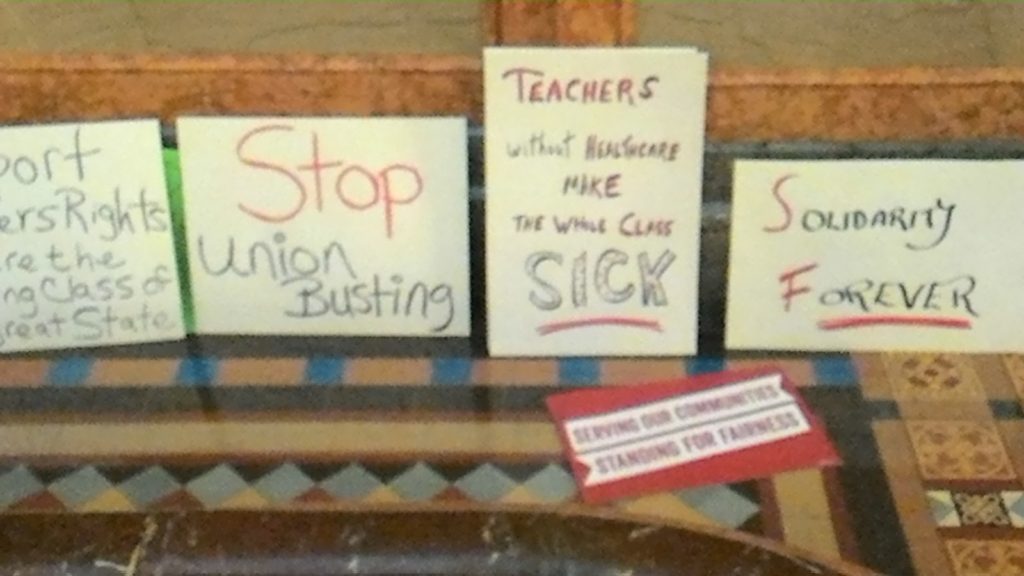

Protest signs left at Iowa Capitol rotunda

Most of Iowa’s hourly public employees, (state and municipal) engaged in various job descriptions, obtained those jobs through the civil service system. Elements of government employees in non-supervisory posts including road crews, office staff, public safety, mechanics, various trades, etc., are part of that system. They have been allowed to unionize and collectively bargain for wages and benefits since the 1970’s. Teacher unions also come under the collective bargaining law.

Many decades ago the so-called merit system (Civil Service) of getting and keeping a job in the public sector, replaced the so-called political spoils system, an at will system, which allowed the placement and duration of employment to be determined by the favoritism of the political powers that be at any given time. It should be noted in objectively comparing the two that a high degree of employment “at will” in the much larger private sector has been a hallmark of Iowa’s and other states with relatively successful economic and unemployment figures.

Willy nilly dismissal of good people happens in the private sector but is not endemic because it is not economic. As regards political hiring, loyalty toward the program is an important factor if policy implementation is involved. Depending on the personality of the employee, obstructionism can descend down to rank and file positions who hold any degree of discretion. And, there is the problem of embedding essentially political jobs or hacks into the Civil Service system to shield them from turnover. *

That being understood, the presumptive grand bargain with public employees that most people took to be the case was that politicians would not up-end personnel placements for ongoing needs in the public sector with every change of the guard. The other presumption was that public employees would stay out of active partisan politics at the level of their employment. This Wikipedia post summarizes some of the political history (excerpt).

Civil Service Reform’ in the U.S. was a major issue in the late 19th century at the national level, and in the early 20th century at the state level. Proponents denounced the distribution of government offices—the “spoils”—by the winners of elections to their supporters as corrupt and inefficient. They demanded nonpartisan scientific methods and credential be used to select civil servants. The five important civil service reforms were the two Tenure of Office Acts of 1820 and 1867, Pendleton Act of 1883, the Hatch Acts (1939 and 1940) and the CSRA of 1978.[1]

There never was much of a practical de jure or de facto fire-wall between the politicians and the public employees as the usual suspects gravitated toward one another and altered, ignored or got around even rudimentary separation. Politicians, the too often sinecure seeking animals that they are, are often willing to use taxpayer money to buy loyalty. And, public employees knowing what side their bread is buttered on, show their “loyalty” through political and financial support in an effort to be the king maker.

Allowing public employees to collectively bargain and de facto collectively and aggressively enter politics were the key precursors to the taxpayer financed, but against taxpayer interest, unholy uneconomic alliance. Beyond wages, allowing bargaining in virtually all matters including benefits has seriously impacted the economics of employment except often in hidden or obscure ways at the time, defying cost estimations and cost controls. The latter has been a particular concern of Iowa’s responsible legislators of late.

In recent weeks, during the “debate” on reforming Iowa’s collective bargaining law, the overreach of the leadership of the public unions and their self-serving tears have been exposed along with their ugly reaction toward those responsible lawmakers. Some solid reforms have passed which we hope will move the state toward financial sustainability to benefit taxpayers and rank and file public employees.

Here are some of the arguments we heard in various convocations we attended and read about along with some responses. We think readers attention to this is still timely because of political threats made by union leaders in forthcoming elections and that the reforms are being challenged in court. Taxpayers will be seeing continued propaganda assaults from the unions.

Facts and arguments, hows and whys, the other side of the coin

What about claims that Iowa public employees have forgone wage increases? How does their compensation compare to the private sector? How was the system “stacked” in favor of unions, and what about political influences?

Amy K. Frantz, Public Interest Institute Vice President wrote on February 9, 2017 on the Mises Institute website:

Why Government Employees in Iowa Are Paid So Much

Iowa has the largest Pay Gap in the nation.

“The Pay Gap” is calculated using Bureau of Labor Statistics data, which gives the average annual wage of a state-government worker and the average annual wage of a private-sector worker for each of the 50 states and the District of Columbia. Our study uses these figures to determine the Pay Gap between the average state-government worker and the average private-sector worker in each state. In 2015, Iowa’s state-government workers received an average wage that was 149.76 percent of what the average private-sector worker in Iowa was paid. Iowa’s Pay Gap was larger than that of any other state or the District of Columbia. That is, state-government employees in Iowa earned relatively more than private-sector workers anywhere in the United States.

One of the reasons for this persistent Pay Gap is that Iowa taxpayers often do not have a seat at the table when unions negotiate contracts on behalf of state-government workers. Iowa’s collective-bargaining laws have stacked the deck against taxpayers. Iowa law states that if negotiations break down, arbitrators “shall” take into consideration the state’s ability to raise taxes in order to pay for an increase in pay for state-government employees. Arbitration in 1991 resulted in a 9 percent raise for state-government employees, despite the state being in the midst of a budget crunch.

Unions representing state-government workers often find themselves sitting across the negotiating table from a friend rather than a representative of Iowa’s taxpayers. Following his defeat in the November 2010 election, then-Governor Chet Culver agreed to a salary increase for the next two fiscal years proposed by the unions representing many state-government employees. Culver simply agreed to the unions’ proposed two-year contract on his way out the door with no negotiations, binding the hands of incoming Governor Branstad and caring little about the taxpayers who would foot the bill.

Then there is the slight-of-hand that results from government double-speak. In fiscal year 2010 (which ran from July 2009 to June 2010), the Des Moines Register reported that unions representing Iowa’s state-government employees agreed to a “zero percent across-the-board salary increase.” This allowed union reps to crow to the press about the sacrifices made by state-government workers. However, under Iowa law, state-government workers were still eligible for merit raises and “step increases,” an automatic increase in pay based on performance and longevity. State-government workers, who “sacrificed” their raises, ended up receiving an average increase of 4.3 percent in salary that year.

Some may say, particularly those working for the state government, that it is not state-government wages that are too high, but rather private-sector wages that are too low. While those of us working in the private sector would always appreciate higher wages, the difference is that in the private sector, a business cannot raise the prices of its goods and services and compel its customers to pay the higher prices. Consumers have the choice to shop elsewhere or not to pay the price at all by not buying that product. However, if the state government needs additional funds to pay its employees, it has the option of raising taxes, and its “customers” — the taxpayers of the state — must pay those higher taxes.

Ms Frantz also authored an extensive analysis for the Public Interest Institute in April of 2014

Iowa’s Privileged Class: State Government Employees

There she addressed another frequently heard argument from public union opponents to any reform:

The argument is often made that state-government workers are paid more because they are generally more highly educated than the average private-sector worker, and state-government workers are typically full-time employees. However, if this is true in Iowa, it is also true across the United States. Iowa’s state government may include judges and football coaches and university physicians – but so does every other state. If Iowa’s annual average wage for private-sector employees includes a larger number of part-time employees than does the state-government sector, this is also true in every other state. If Iowa has a Pay Gap because of these differences, every other state should have a Pay Gap of a similar size. But Iowa’s Pay Gap is larger by far than any other state. These differences may explain, in part, why there is a Pay Gap, but they do not explain why Iowa’s Pay Gap is so much larger than in other states and is the largest in the nation!

Fortunately, as result of reforms passed, if negotiations break down, no longer “may arbitrators take into consideration the state’s ability to raise taxes in order to pay for an increase”.

Interestingly the state’s public teacher union, the Iowa State Education Association (ISEA), while not wanting to talk about the public/private gap, was vociferous in talking about state to state average teacher wage “gaps” as part of their propaganda leading up to the dramatic increase in teacher salaries foisted on Iowa taxpayers in 2007. Then they wanted to compare gaps between salary averages for public school teachers here and the nation as a whole. We say foisted because the propaganda was a gross distortion of economic reality. As we responded at the time to the Quad City Times’ constant repeating of the ISEA drivel:

Readers would be better served if news stories concerning Iowa teacher salaries included a more objective perspective than simply that of the ISEA teacher union press releases. Whether the theme of the press releases is that Iowa is 40th or 42nd in raw national rankings, it is pure sensationalism to give the impression to the tax-paying public that our state is egregious in what it pays teachers, or indeed that 40th or 42nd are meaningful figures at all.

What is conveniently not part of teacher union press releases is that Iowa teacher salaries, on average, are near the top for our region. Using ISEA figures for 2004-2005, the latest state-by-state figures posted on their Web site, less than $200 annually separates Iowa teacher salaries from the highest state in our six-state region (Plains States). The order of compensation on a regional basis from highest to lowest is Nebraska, Iowa, Kansas, Missouri, North Dakota and South Dakota.

The national array of compensation figures and averages are heavily skewed by states that have extraordinary costs of living figures and are apparently in the hip pockets of public unions to boot. Hawaii, California, Connecticut, Illinois (skewed by Chicago) and others heavily skew the mean average. Adjusted for cost of living comparisons back then, Iowa ranked about in the middle nationwide.

In the more recent controversy, we only got snorts and mumbles and subject changes when we raised the matter of Iowa’s declining educational scores and the relationship to increased teacher salaries. Iowa used to be perennially near the top and is now 17th.

Ms Franz addressed the issue of the gap in wages, public to private, being due to public employees having jobs that supposedly required more education. Her point was excellent in that such education levels if relevant would likely be true in every state and yet Iowa’s gross gap remains the highest. Nevertheless we frequently heard caterwauling by public employees at events we attended that they have this degree and that advanced degree and yet only make a pittance . . . can’t pay for their loans . . . and more gnashing of teeth. Some were teachers and some were social workers of one sort or another.

As we tried to gently suggest to them in between their literally in-our-face shouting, in and of itself the legislation proposed (and passed) has nothing to do with levels of compensation or benefits, only what the state is required to negotiate and how arbitration would proceed. The well managed state has no interest in making compensation inadequate to get the job done, to get and keep qualified people.

Next installment —

- More on job comparisons

- A couple of vignettes from the legislative forums and protests

- Who shows up, who do the legislature hear from on these issues.

- Other related topics

*While Iowa’s limited legislative attempts at collective bargaining reform are the focus of this post, “grander” Civil Service reform, and its history, is an important topic addressed in this article: Civil Service Reform Explained